Fed Bypasses Emergency-Loan Policy on Rate for Securities Firms

By Scott Lanman

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601109&sid=ahTWr7zZgD3Q&refer=home

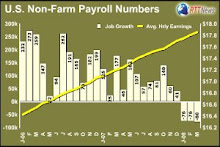

March 20 (Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve bypassed its own emergency-lending policies to let securities firms borrow at the same interest rate as commercial banks as the central bank sought last weekend to stave off a financial-market meltdown.

Guidelines revised in 2002 say the Fed should charge non- banks more than the highest rate that commercial banks pay. Instead, Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and his colleagues, in emergency votes on March 16, invoked broader authority in the Federal Reserve Act to give Wall Street dealers the same rate as banks, a Fed staff official said on condition of anonymity.

Backstopping securities firms, coupled with last week's action to keep Bear Stearns Cos. afloat before its sale to JPMorgan Chase & Co., represent the central bank's first lifelines to institutions other than banks since the Great Depression.

``They certainly pushed the limit,'' said Brian Sack, a former Fed researcher who is now senior economist at Macroeconomic Advisers LLC in Washington. The law probably has ``enough gray area'' to allow the decision, he said.

Bernanke raced to unveil the steps before trading on the Tokyo Stock Exchange began on March 17. The weekend action, timed to complement JPMorgan's rescue of Bear Stearns, included a cut in the so-called discount rate and the opening of borrowing to the primary dealers in Treasury securities, not all of which are banks.

Regulatory Navigation

``They used what authorities they thought they had and went ahead,'' said Oliver Ireland, who worked as a Fed counsel for more than two decades and is now a partner at Morrison & Foerster in Washington. ``From a public-policy standpoint, if this is important to do, you wouldn't want to be tripped up by your own regulatory structure.''

The changes were the Fed's most aggressive response to the 8-month-old credit squeeze that's worsening the housing recession and the economic slowdown. Bear sought the Fed's help after a run on the firm, the second-largest underwriter of U.S. mortgage-backed securities.

Not every former Fed employee was as forgiving. The Fed's haste in setting aside its own guidelines is ``troubling,'' said Vincent Reinhart, who worked at the central bank between 1983 and 2007 and is now a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

``The regulation is very clear as to the circumstances of the loan, and it is odd that they wouldn't apply a regulation that would seem to encompass what they want to do,'' said Reinhart, who served as head of the Division of Monetary Affairs under Bernanke and his predecessor Alan Greenspan.

Imposing Penalty

The 2002 guidelines say that non-banks may only receive emergency cash ``at a rate above the highest rate in effect for advances to depository institutions.'' That means securities firms may normally have to pay more than the current 3 percent rate reserved for banks that are less financially sound.

In deciding to charge securities firms such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley and Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. the same rate as commercial banks, the Fed used 1920s-era authority provided by Congress to set interest rates that the law says ``shall be fixed with a view of accommodating commerce and business,'' the Fed staff official said.

The Fed will give the first glimpse of how much banks and securities firms are borrowing under the new programs when it releases weekly money supply data at 4:30 p.m. in Washington.

Seeking Order

In its March 16 statement, the Fed said the lending was ``designed to bolster market liquidity and promote orderly market functioning. Liquid, well-functioning markets are essential for the promotion of economic growth.''

The Fed reduced the primary discount rate March 18 by 0.75 percentage point to 2.5 percent. The secondary rate, offered to more-distressed banks, is a half-point higher, at 3 percent.

The federal funds rate, the more closely-watched U.S. short-term benchmark, was cut by the same margin to 2.25 percent.

In December, the Fed went around requirements for prior notice and public comment when writing the regulations to authorize new funding auctions. The Fed's statement then said any delay caused by following standard procedures would have been ``contrary to the public interest.''

The central bank's regulations were revised in 2002, as part of a decision to make the discount rate higher instead of lower than the federal funds rate, removing a long-standing subsidy.

The Fed hadn't previously taken advantage of the power to let individuals, partnerships and companies borrow since the 1960s, when it authorized lending to savings institutions that weren't covered by the Fed at the time. The banks didn't draw on the loans.

``The Federal Reserve Act is somewhat obsolete today,'' and that's why Fed officials probably had to take such action, said Sack of Macroeconomic Advisers.

Friday, March 21, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

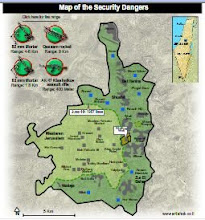

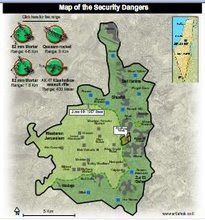

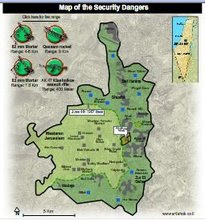

Divided Jerusalem

+and+Iran%27s+Ahmadinejad.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+and+FM+Livni.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment